Sergio Larraín - The Photographer Who Walked Away

- Arnold Plotnick

- Dec 2, 2025

- 4 min read

Every so often, you discover a photographer who feels like they’ve been quietly waiting for you — their images familiar the instant you see them. That’s how I felt encountering Sergio Larraín, the enigmatic Chilean street photographer who seemed to materialize, and then disappear, like a meteor.

I can’t claim to have been consciously aware of Larraín’s work. Six years ago, when Thames & Hudson published Magnum Streetwise: The Ultimate Collection of Street Photography, I bought it immediately. It profiled thirty great street photographers, from Erwitt to Davidson to Parr. Larraín had a half-page bio and just seven photos — five from Sicily, two from Peru. They barely registered.

So, when I saw that the International Center of Photography in New York was mounting an exhibition titled Sergio Larraín: Wanderings, I went more out of curiosity than expectation. By the time I left, he’d secured a permanent place on my personal short list.

A Life of Seeing

Born in 1931 to a prominent Santiago family, Larraín grew up surrounded by art and architecture. His father was a celebrated architect and collector; their home overflowed with paintings and pre-Columbian artifacts. Yet Sergio, restless by nature, studied forestry in California instead of art. He bought a Leica only because he thought it was “the most beautiful object” he could own — and then, improbably, used that object to redefine how beauty itself could be perceived.

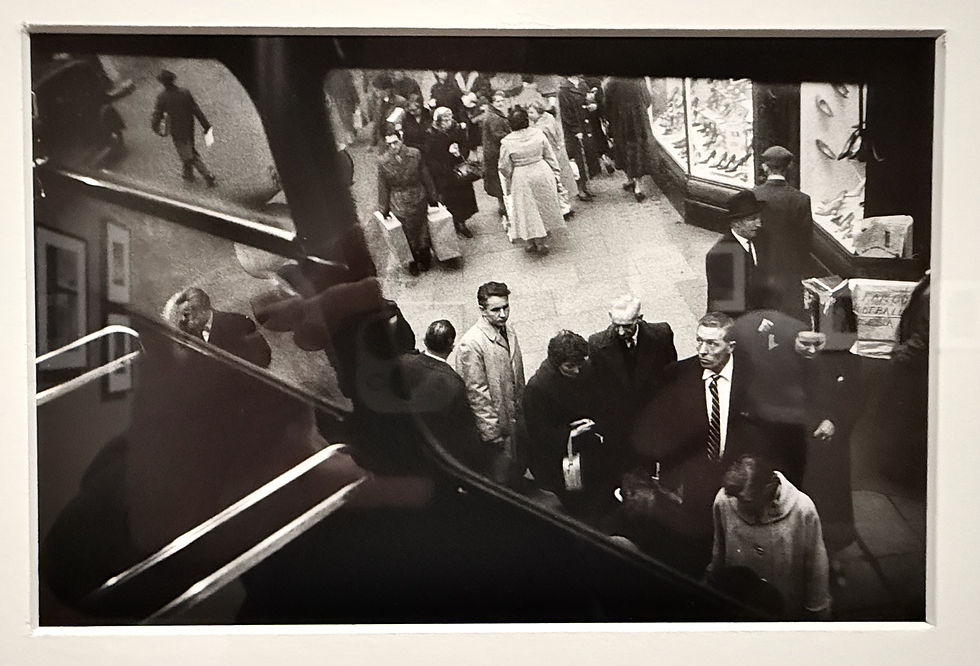

Back in Chile, he began photographing street children in Santiago and Valparaíso — the “vagabond kids,” as he called them. The tenderness in those images is disarming. They’re unsentimental yet poetic, filled with empathy but never pity. In 1956, when MoMA purchased two of his prints, the validation pushed him fully toward photography. (Try as I might, I haven’t been able to find which two prints they purchased.) Two years later, a British Council grant sent him off to London, where he made foggy, melancholic pictures of postwar England — reflections, bowler hats, and blurred commuters. Henri Cartier-Bresson saw them, recognized a kindred spirit, and invited him to join Magnum Photos. (Cartier-Bresson famously said, “Sharpness is a bourgeois concept.” So Larraín’s selective use of blur, which really struck me in some of the exhibited photos, probably impressed him.)

The State of Grace

I know it’s cliché to describe photos as dreamlike, but Larraín’s photographs have that aura. He was fascinated by the way light can make things look otherworldly: shadows falling like curtains, figures half-hidden behind doorways, moments that feel both candid and composed. In Valparaíso he captured his most famous image — two girls descending a narrow staircase, one stepping into a trapezoid of light, the other following behind in shadow, a bottle glinting in her hand. “It was a magical moment,” he said later. “A good image is born from a state of grace.”

Standing in front of that print and others at ICP, I found myself pondering how effortlessly he used composition to elicit emotion. Leading lines, bold diagonals, blurred fore- and backgrounds — every compositional choice pulls you inward, yet nothing feels contrived. He could shoot in blinding sun or near-darkness, on the ground or from a rooftop, and still make the scene resonate. In many of his photos, heads are cut off, figures move in and out of frame, but rather than feeling careless, it feels alive. Whether these photos were SOOC (straight out of the camera) or not, I can’t say — but they have that feel, raw and immediate. If you believe that street photography is, as someone once said, “the photojournalism of everyday life” (a notion Cartier-Bresson would have understood), then Larraín embodied it. His pictures remind you that everyday life is anything but ordinary.

Withdrawal and Revelation

By the late 1960s, weary of deadlines and the grind of assignment work, he left Magnum, retreated to the Chilean mountains, and turned inward — yoga, meditation, mysticism. “Grace comes when you are delivered from conventions, obligations, conveniences, competition,” he wrote. “You walk around in surprise, seeing reality as if for the first time.” That sentence feels like the key to his art. You can sense a desire to disappear into the act of seeing, to dissolve the boundary between observer and observed. Many of his frames seem to hover between clarity and mystery, as if something more waits just outside the frame. Good street photography is really just good storytelling, and Larraín was a master at it — every frame hints at a larger world beyond the edge of the image.

After the Camera

Larraín died in 2012, after decades of near solitude. His archive is small — just a few thousand negatives — but each one glows with that “grace” he described, the state of openness that let him see without striving. At the ICP show, I found myself thinking he had achieved what most of us never do: the ability to stop searching once the vision was found.

Referring to his photos, Larraín once advised, “Follow your own taste and nothing else.” For a man who walked away from everything, it’s clear he took that advice to heart in life as well as art. I think of that quote as his final photograph — a self-portrait in words.

The ICP exhibit Sergio Larraín: Wanderings runs through January 2026.

Comments